I graduated last year with a bachelor’s degree in what is called “Film Studies,” because a majority of the movies we watched and wrote about were shot on film. I also grew up in what will be the last generation to have seen a major motion picture premiere that was originally shot and edited on film. As I re-read Murch’s book this semester I was struck by how it knit together my previous education of film with my new path as a student of design and technology. His work clearly laid out the advantages and disadvantages of both film and video; and though certain problems associated with video have been remedied by more reliable computing environments, the connection to a “kinetic feedback” with video footage has become increasingly distant. My project, the Videola, is an attempt to reclaim that connection.

I decided to focus the Videola’s function to the primary decision made by an editor: where to cut. Murch compares this task to that of a gunslinger; focusing with one’s entire body, waiting for the perfect moment to begin and end a scene.

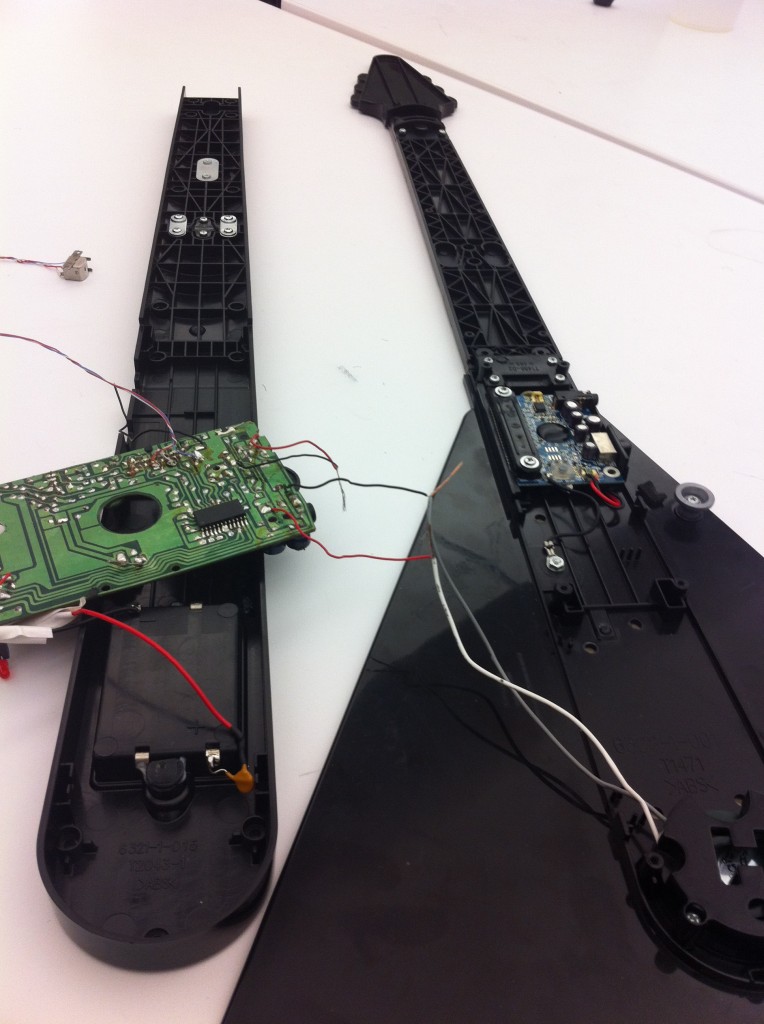

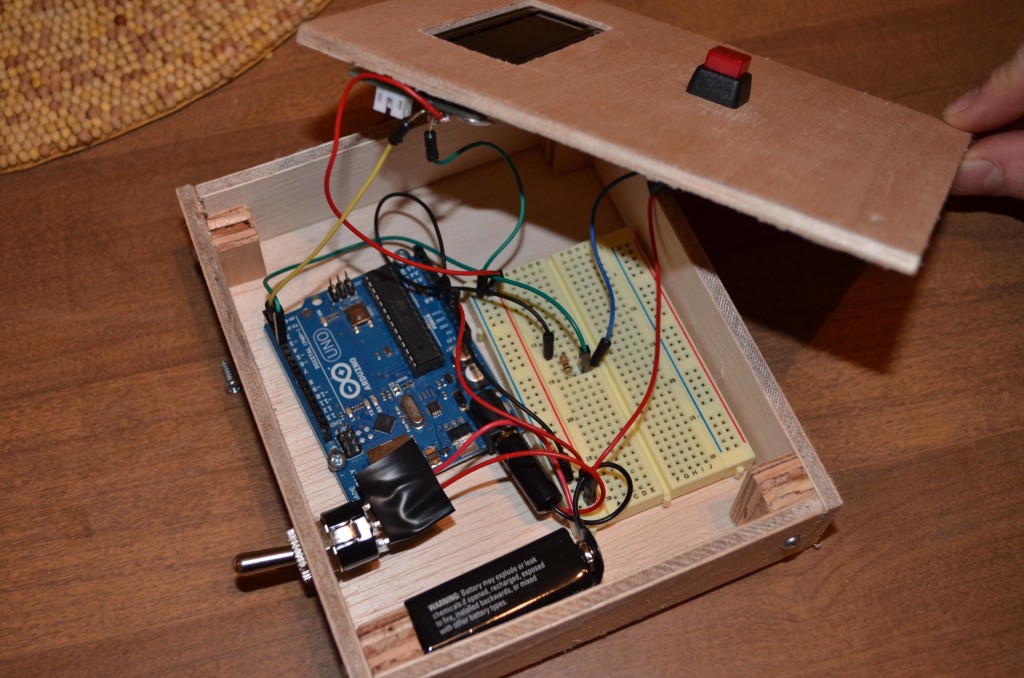

I began the project by outlining the physical elements I would need (a hand crank mechanism, rotary encoder, Arduino, and switches) and writing pseudo code for the software elements. I intentionally delayed creating the wooden housing until I was certain all the elements of the prototype would work together as planned. For the first several weeks my desk served as housing for the circuitry, allowing me to experiment quickly with various was of integrating the data coming from Arduino into openFrameworks. During this prototype phase I acquired the film winders of an authentic Moviola, the film editing machine whose namesake I reference in my own project. The weight and sturdiness of their metal construction served as a perfect tactile interface for my rotary encoder.

The Videola project opens the way to numerous avenues of exploration. The primary concern in further iterations is to contain all the functions of the machine into a succinct apparatus. A USB port built into the body of the machine would allow the user to swap ‘reels’ without handling the computer itself. A projector built into the workings of the machine would strengthen the connection of user and medium by removing the distraction of a physical monitor. Once these aesthetic concerns have been addressed, it will be possible to move to questions of function. Instead of the workflow ending in the physical world, perhaps the Videola could upload completed pieces to YouTube, Vimeo, or Facebook; retaining the mobility of video without sacrificing the physical connection in the edit process.

In every iteration it is my hope that users who experience working with the Videola will feel an emotional connection not only with the footage they are editing but also with the history of film editing itself. Future colleagues of mine may very soon have diplomas with “Video Studies,” inked on them, but it will be my goal to ensure that whatever medium we use can still be a passionate and beautiful representation of the many stories the future will have to tell.